Do you have a problem? Write a compiler!

These are notes of the talk I gave at ClojuTre 2019. There is a video recording of the talk, and the slide deck as a PDF.

Hello ClojuTre. I'm Oleg from Helsinki.

Imagine you are writing a cool new rogue-like game. So cool many have no idea what's going on. A definitive character of rogue-likes is procedural generation of content. You'll need a random number generator for that.

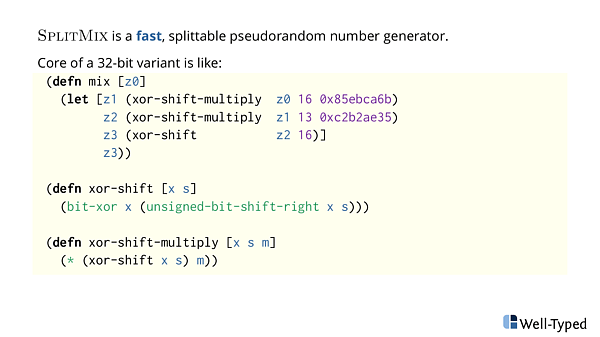

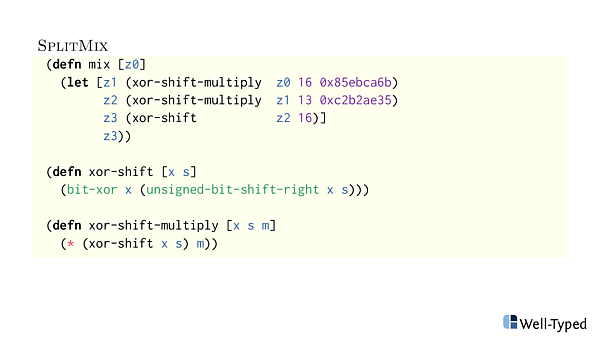

SplitMix is a fast, splittable pseudorandom number generator. Being able to split a generator into two independent generators is a property you'll want if you use the generator in a functional programming language. Look it up. We'll concentrate on the being fast part. Obviously you want things to be fast.

SplitMix is fast. It does only 9 operations per generated number, one addition to advance the random seed, and xor, shift, multiply xor, shift, multiply, xor and shift. 9 in total.

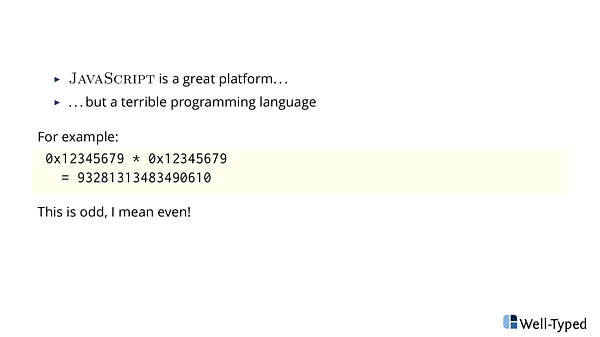

However, for the maximum reach, we want our game to run in the web browsers.

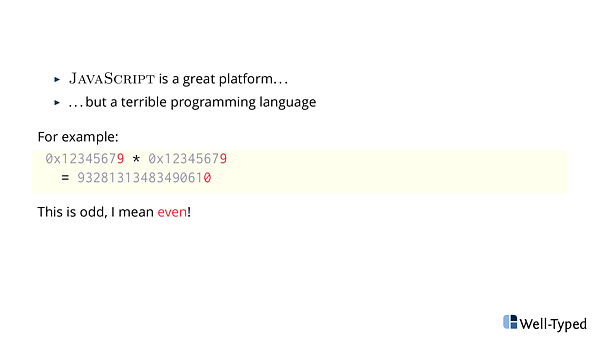

- JavaScript is a great platform

- But a terrible programming language

Look carefully. When we multiply two "big" odd numbers, we do get even result. We shouldn't: product of two odd numbers is odd.

JavaScript numbers are a mess. Next a bit of arithmetics.

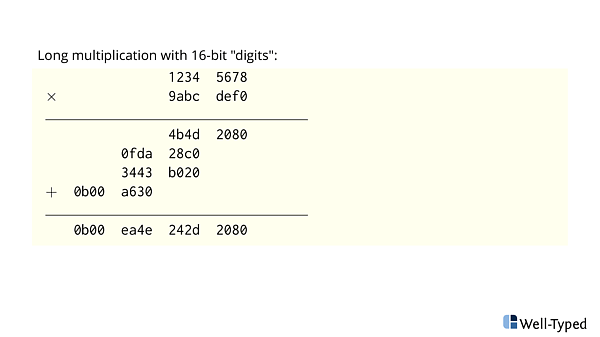

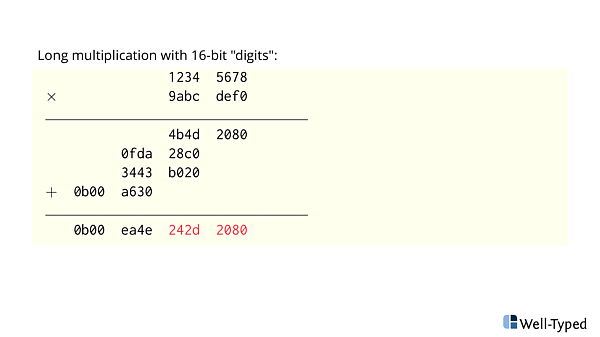

Instead of multiplying two big numbers, we split them in high and low parts and multiply many small numbers. Like in an elementary school. Then we'll have enough precision.

So as we are multiplying 32bit numbers, and are interested only in lower 32 bits of 64 bit result. Then we need to do only three multiplications.

At the end, we can get correct results, i.e. good random numbers even in JavaScript.

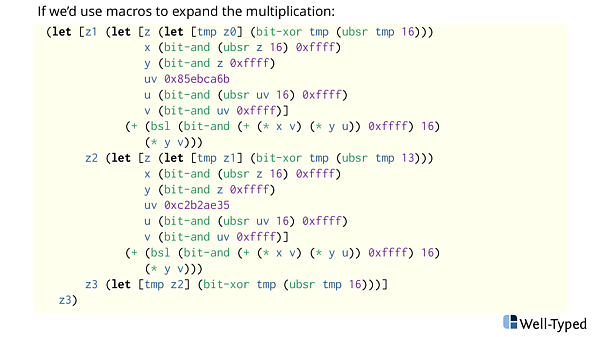

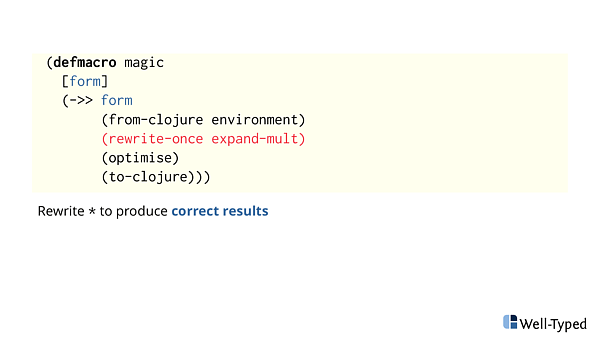

Next if we replace the multiplication in xor-shift-multiply with a macro doing the right thing, and actually change everything to be a macro, and expand we'll get...

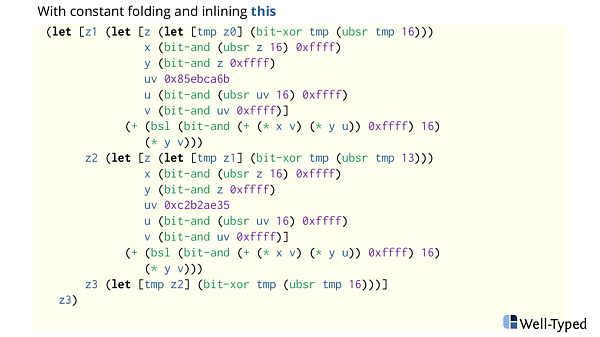

a lot of code which barely fits on the slide.

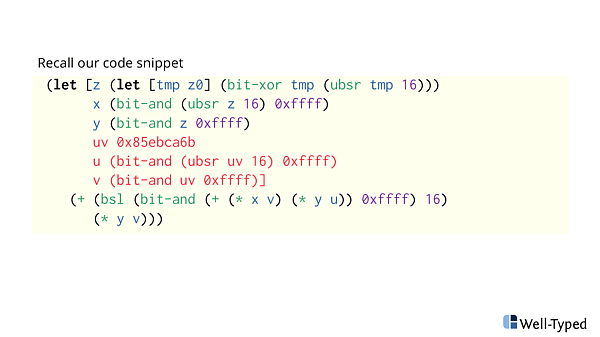

I had to shorted bit-shift-left to bsl and unsigned-bit-shift-right to ubsr.

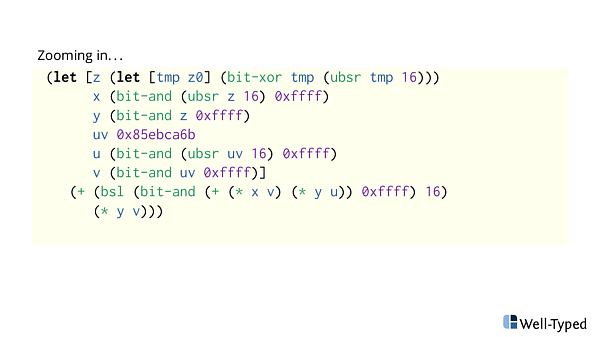

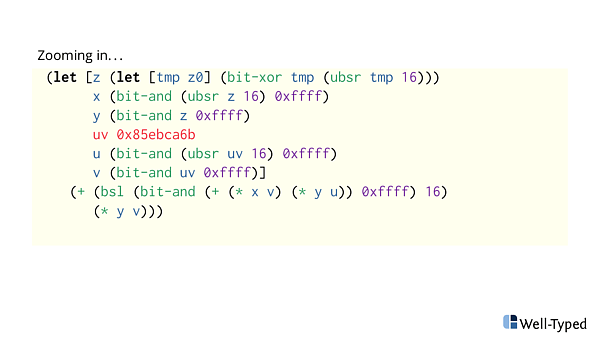

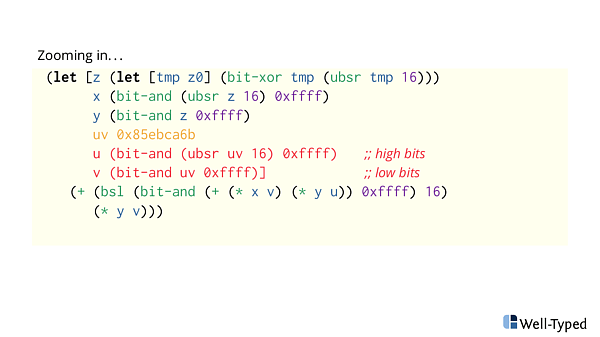

Look closely. Would you write this kind of code.

We bind ("assign") a constant value to uv variable.

And the calculate the high and low 16 bit parts of it. Something we could write directly: let [u 0x85eb v ca6b], i.e. optimize by hand. Should we do so?

No. Let's rather write an (optimizing) compiler. We don't have time to optimize by hand.

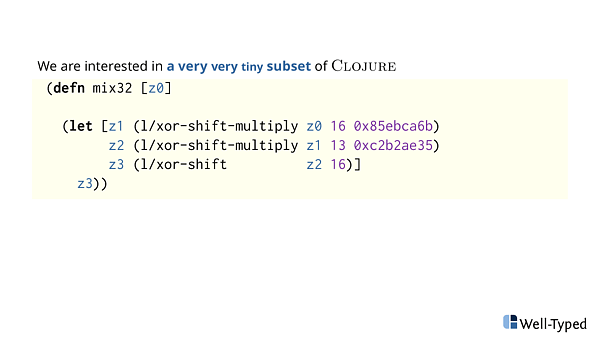

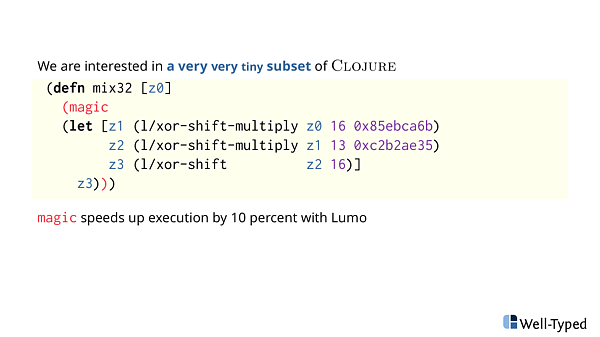

Recall, we have a very specific problem. Working with a very very tiny subset of Clojure. Some simple arithmetic and bit mangling of 32bit numbers.

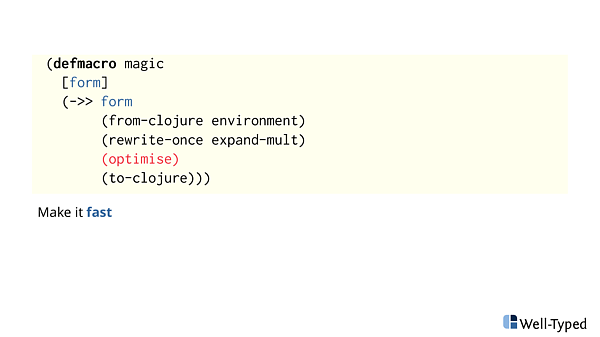

We'd like to add a little of magic, which would make the program magically run faster. In my toy-micro benchmarks the speed-up is 10 percent. It's definitely worth it.

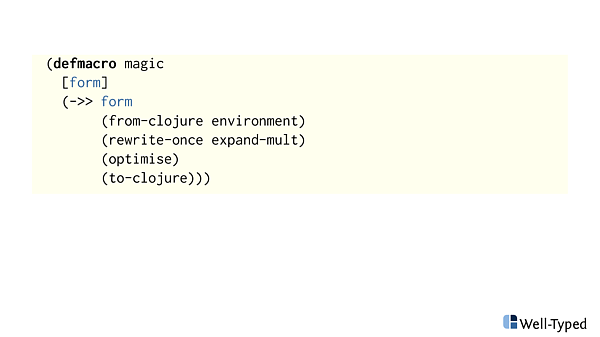

What is this magic?

A little cute macro. Of course.

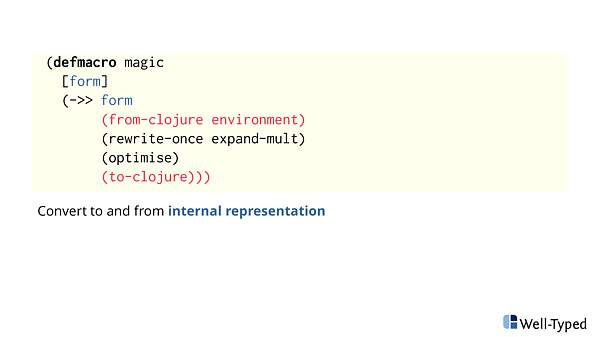

We get a form and convert it into internal representation on a way in, and back to Clojure on the way back.

Working the whole Clojure syntax directly is insane task. We want only deal with a small sane subset of it. Also in a easier to manipulate format. Clojure as a pragmatic language is still optimized for writing and reading, not machine manipulation so much.

The next step is to expand a multiplication using a trick we have seen previously. We could have done it already in from-clojure step, but it's good engineering to have only one thing per step.

And the important part is the optimise function.

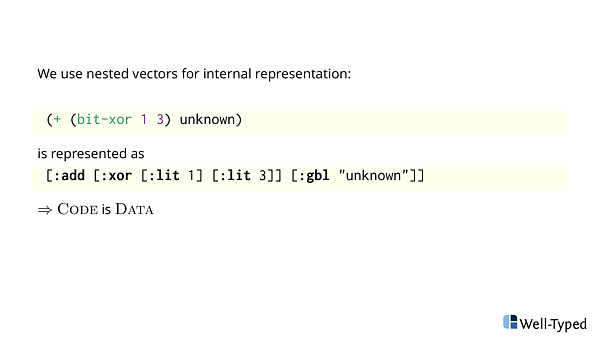

The internal representation I used is nested vectors with a node type as a first element. An uniform representation made it way easier to do everything else. Note how literals 1 and 3 are wrapped into vector too. We can simply look at the head of a vector to know what we are dealing with.

Code is Data.

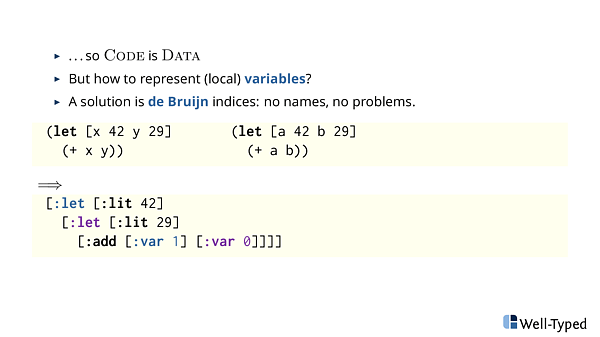

A difficult part in Code is Data are local variables. I chose to use de Bruijn indices, so instead of names: x and y or a and b there are numbers counting towards the corresponding let (which binds only one variable at the time by the way).

de Bruijn indices are tricky to grok. Look at the colors, they are there to help. The blue :var 1 references "one away" let.

I don't expect you to understand them. It's one way to represent bindings. Perfectly there should be a library, so you don't need to think about low-level details.

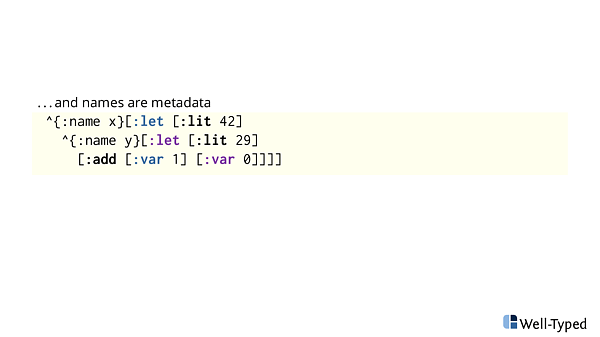

Once we got rid out of names, we can still keep them around using metadata. That's a really cool feature in Clojure, I have to admit. The metadata is there, but not in your way. And having names around is actually useful when you try to debug things.

Now we have a setup done. Let's jump into optimizations.

Recall our code snippet. There's uv which is bound to a constant. And then it's used an expression which could simplify if we do this and that...

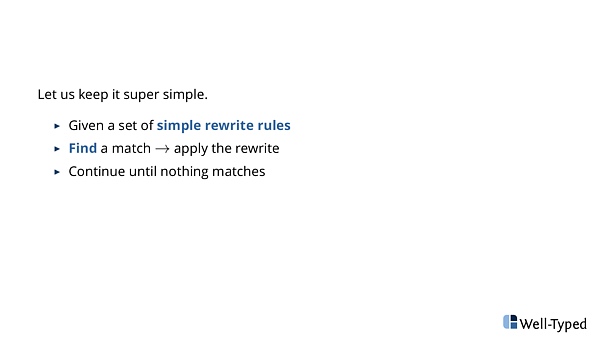

Let's keep it super simple.

- We can have a small set of simple local rewrite rules. Local meaning, we don't need to look around, only at one subexpression at the time.

- Then we try to match the rule everywhere, and if it match, perform the rewrite.

- And loop until there's nothing to do.

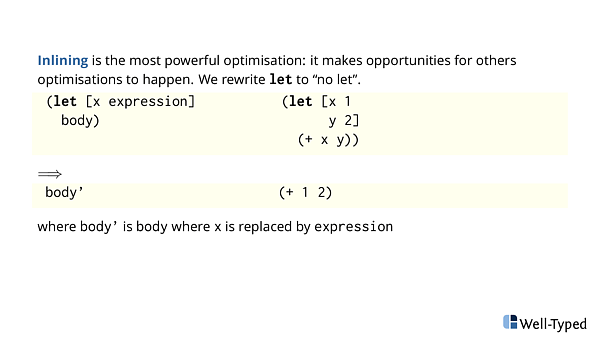

The first optimization is inlining. In a sense it's most powerful one, as it makes opportunities for other optimizations to fire, even that on itself it doesn't do much.

So if we have a let-binding, then in some cases we perform a substitution. Replace all xs with an expression inside a body.

let x 1 y 1 (+ x y) to a lot simpler (+ 1 2). But nothing more, just that.

I need to point out, that optimizing is somewhat of an art. Sometimes it work, sometimes it don't.

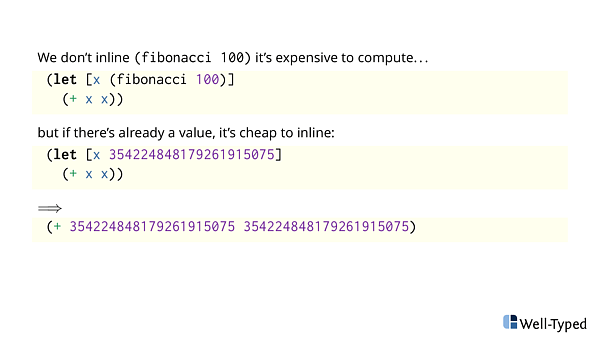

For example, we don't want to duplicate an expensive (fibonacci 100) expression. We want to evaluate it once and share the result.

On the other hand, if someone already went and computed the value, then we can push it to the leaves of an expression tree.

Heuristics are tricky.

Luckily for our needs simple heuristics work well.

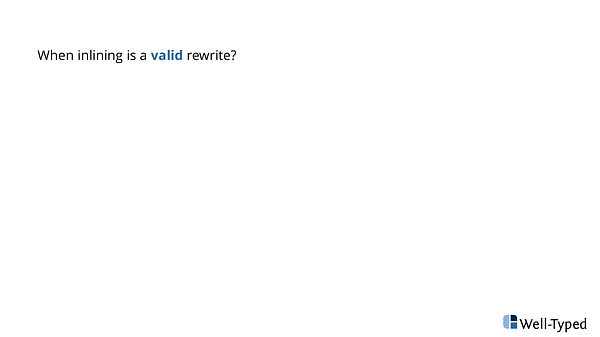

When inlining is a valid rewrite?

Not in every language. Consider this not-so-functional example.

If we substitute everything, the (do-foo) and (do-bar) would be in different order. And (do-quux) will be gone completely, hopefully it didn't anything important!

We need a language where there are no side-effects, nor there are so much difference in the execution order. Whole Clojure isn't such language. Our tiny subset is.

I have heard there are programming languages which behave like our small one, but are more general purpose!

OK. Let's move to the next optimization.

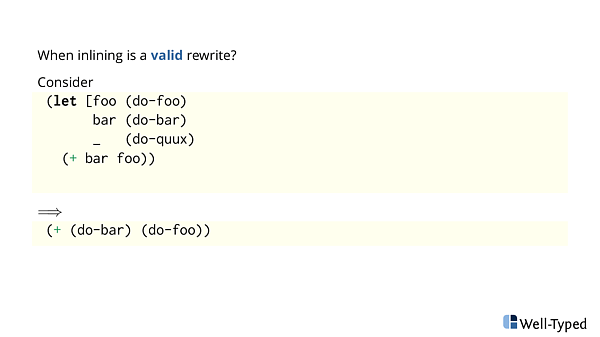

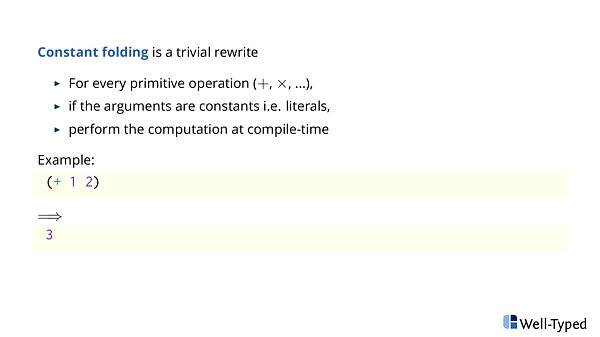

When we have something simple as (+ 1 2), let us evaluate it already at compile time.

For every primitive operation, if the arguments are known constants, just do it.

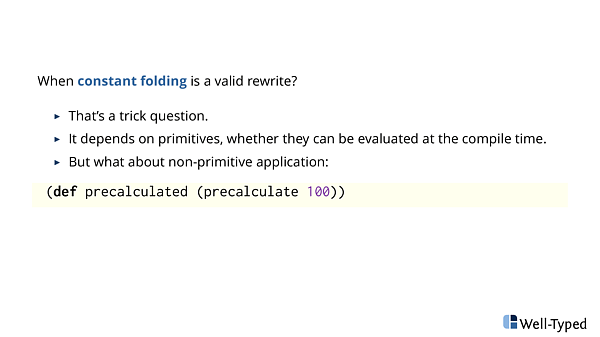

Now, I ask you when constant folding is a valid rewrite.

Well, that was a trick question. It really depends on primitives, whether it make sense to perform them at compile time. (Even pure languages have primitives to print stuff on a screen).

But you could think about that precalculate example. When does it makes to perform the calculation (assuming we somehow know it terminates):

- At compile time?

- At start up?

- At first access?

It really depends, and there are no single simple answer.

Again, optimizations is an art.

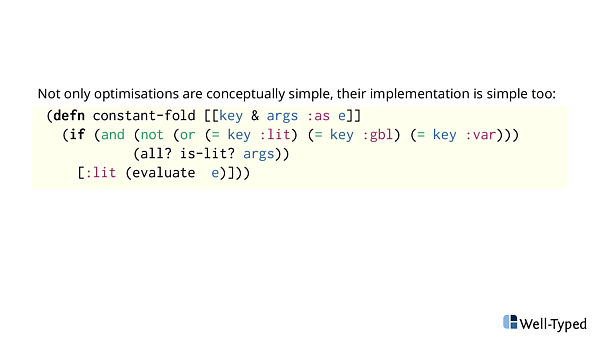

Because we work with nice internal representation, writing individual optimizations is so nice.

- if a node is not one of special nodes

- and all node arguments are constants

- evaluate it.

The code is shorter than my explanation. And still understandable.

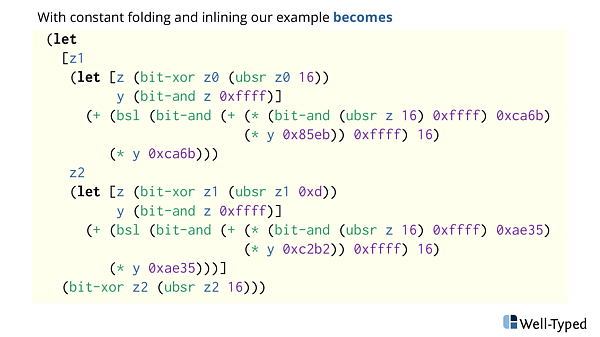

With these two optimizations, inlining and constant folding, we get from this big (and repetitive) code blob to...

Something which actually fits on the slide without font size scaling. It's not super-pretty, but it's hard to spot if something can be done there.

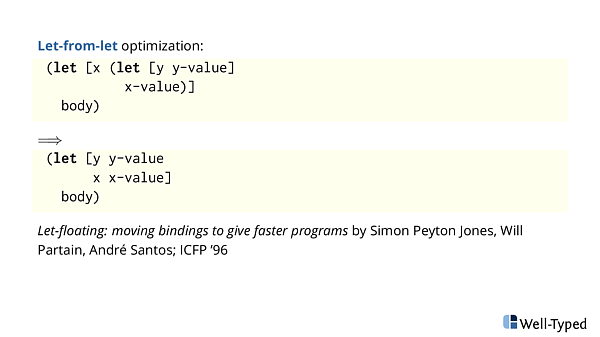

We can make it look nice with one more optimization. When you bind a let-expression to a variable in outer let-expression, we can float out the inner one.

A very old idea it is.

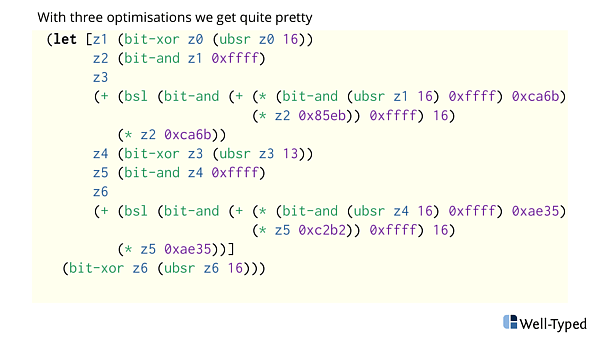

And then we get (in my opinion) a very nice direct code. Six intermediate results to get final one.

That's what I wanted to tell you.

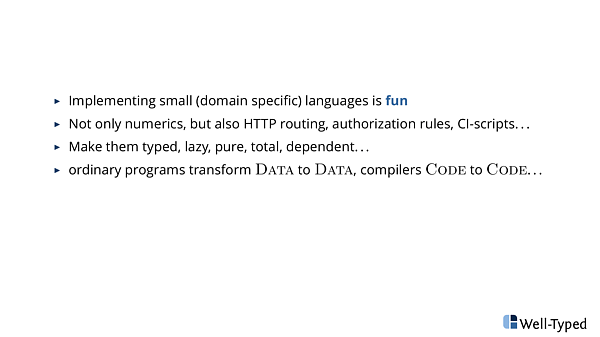

- Implementing small (domain specific) languages is fun.

- If you approach problems with "let's write a programming language to describe them" -attitude there a lot of big hammers in your disposal. A lot of wheels is already invented.

- Languages don't need only be about numerics, it could be HTTP routing, authorisation rules, UI-workflows, CI-scripts (I could bash about bash), data descriptions, you name it.

- But make your languages typed, lazy, pure, total or and even dependent for extra fun and interesting new problems. ;)

Thank you.

- 2025-02-13 – PHOAS to de Bruijn conversion

- 2025-02-11 – NbE PHOAS

- 2024-06-24 – hashable arch native

- 2024-05-28 – cabal fields

- 2024-04-21 – A note about coercions